Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model

OSI Reference Model

Network Reference Models

OSI , osi

As computer network communication grew, the need for a consistent standard for vendor hardware and software became apparent.

Thus, the first development of a network reference model began in the 1970’s, by an international standards organization.

A network reference model serves as a blueprint, dictating how network communication should occur. Programmers and engineers design products that adhere to these models, allowing products from multiple manufacturers to interoperate.

Network models are organized into several layers, with each layer assigned a specific networking function. These functions are controlled by protocols, which govern end-to-end communication between devices.

Without the framework (standards and protocols) that network models provide, all network hardware and software would have been proprietary. Organizations would have been locked into a single vendor’s equipment, and global networks like the Internet would have been impractical or even impossible.

The two most widely recognized network reference models are:

• The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model

• The Department of Defense (DoD) model

The OSI model was the first true network model, and consisted of seven layers. However, the OSI model has become criticized over time, replaced with more practical models like the TCP/IP (or DoD) reference model.

Network models are not physical entities. For example, there is no OSI device. Devices and protocols operate at a specific layer of a model, depending on the function. Not every protocol fits perfectly within a specific layer, and some protocols spread across several layers.

OSI Reference Model

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model was developed in the 1970’s and formalized in 1983 by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). It was the first networking model, and provided the framework governing how information is sent across a network.

The OSI Model (ISO standard 7498) consists of seven layers, each corresponding to a particular network function:

|

7

|

Application Layer

|

|

6

|

Presentation Layer

|

|

5

|

Session Layer

|

|

4

|

Transport Layer

|

|

3

|

Network Layer

|

|

2

|

Data-Link Layer

|

|

1

|

Physical Layer

|

Various mnemonics have been devised to help people remember the order of the OSI model’s layers:

|

7

|

Application Layer

|

All

|

Away

|

|

6

|

Presentation Layer

|

People

|

Pizza

|

|

5

|

Session Layer

|

Seem

|

Sausage

|

|

4

|

Transport Layer

|

To

|

Throw

|

|

3

|

Network Layer

|

Need

|

Not

|

|

2

|

Data-Link Layer

|

Data

|

Do

|

|

1

|

Physical Layer

|

Processing

|

Please

|

The ISO further developed an entire protocol suite based on the OSI model; however, this OSI protocol suite was never widely implemented. More common protocol suites can be difficult to fit within the OSI model’s layers, and thus the model has been mostly disapproved.

A more practical model was developed by the Department of Defense (DoD), and became the basis for the TCP/IP protocol suite (and subsequently, the Internet).

The OSI model is still used predominantly for educational purposes, as many protocols and devices are described by what layer they operate at.

The Upper Layers

The top three layers of the OSI model are often referred to as the upper layers. Thus, protocols that operate at these layers are usually called upperlayer protocols, and are generally implemented in software.

The function of the upper layers of the OSI model can be difficult to visualize. The upper layer protocols do not fit perfectly within each layer; and several protocols function at multiple layers.

The Application layer (Layer 7) provides the actual interface between the user application and the network. The user directly interacts with this layer. Examples of application layer protocols include:

• FTP (via an FTP client)

• HTTP (via a web-browser)

• SMTP (via an email client)

• Telnet

The Presentation layer (Layer 6) controls the formatting of user data, whether it is text, video, sound, or an image. The presentation layer ensures that data from the sending device can be understood by the receiving device.

Additionally, the presentation layer is concerned with the encryption and compression of data. Examples of presentation layer formats include:

• Text (RTF, ASCII, EBCDIC)

• Music (MIDI, MP3, WAV)

• Images (GIF, JPG, TIF, PICT)

• Movies (MPEG, AVI, MOV)

The Session layer (Layer 5) establishes, maintains, and ultimately terminates connections between devices. Sessions can be full-duplex (send and receive simultaneously), or half-duplex (send or receive, but not simultaneously).

The four layers below the upper layers are often referred to as the lower layers, and demonstrate the true benefit of learning the OSI model.

The Transport Layer

The Transport layer (Layer 4) is concerned with the reliable transfer of data, end-to-end. This layer ensures (or in some cases, does not ensure) that data arrives at its destination without corruption or data loss.

There are two types of transport layer communication:

• Connection-oriented – parameters must be agreed upon by both parties before a connection is established.

• Connectionless – no parameters are established before data is sent. Parameters that are negotiated by connection-oriented protocols include:

Flow Control (Windowing) – dictating how much data can be sent between acknowledgements

Congestion Control

Error-Checking

The transport layer does not actually send data. Instead, it segments data into smaller pieces for transport. Each segment is assigned a sequence number, so that the receiving device can reassemble the data on arrival. Examples of transport layer protocols include Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP).

Sequenced Packet Exchange (SPX) is the transport layer protocol in the IPX protocol suite.

The Network Layer

The Network layer (Layer 3) has two key responsibilities. First, this layer controls the logical addressing of devices. Logical addresses are organized as a hierarchy, and are not hard-coded on devices. Second, the network layer determines the best path to a particular destination network, and routes the data appropriately.

Examples of network layer protocols include Internet Protocol (IP) and Internetwork Packet Exchange (IPX). IP version 4 (IPv4) and IP version 6 (IPv6) are covered in nauseating detail in separate guides.

The Data-Link Layer

The Data-Link layer (Layer 2) actually consists of two sub-layers:

• Logical Link Control (LLC) sub-layer

• Media Access Control (MAC) sub-layer

The LLC sub-layer serves as the intermediary between the physical link and all higher layer protocols. It ensures that protocols like IP can function regardless of what type of physical link is being used.

Additionally, the LLC sub-layer can use flow-control and error-checking, either in conjunction with a transport layer protocol (such as TCP), or instead of a transport layer protocol (such as UDP).

The MAC sub-layer controls access to the physical medium, serving as mediator if multiple devices are competing for the same physical link.

Specific technologies have various methods of accomplishing this (for example: Ethernet uses CSMA/CD, Token Ring utilizes a token).

The data-link layer packages the higher-layer data into frames, so that the data can be put onto the physical wire. This packaging process is referred to as framing or encapsulation. The encapsulation type used is dependent on the underlying data-link/physical technology (such as Ethernet, Token Ring, FDDI, Frame-Relay, etc.)

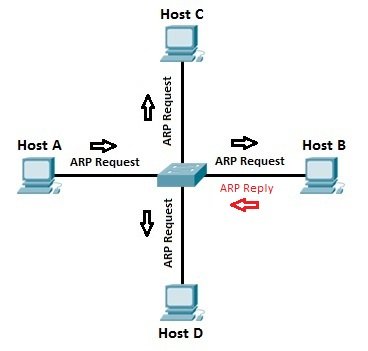

Included in this frame is a source and destination hardware (or physical) address. Hardware addresses usually contain no hierarchy, and are often hard-coded on a device. Each device must have a unique hardware address on the network.

The Physical Layer

The Physical layer (Layer 1) controls the transferring of bits onto the physical wire. Devices such as network cards, hubs, and cabling are all considered physical layer equipment.

Explanation of Encapsulation

As data is passed from the user application down the virtual layers of the OSI model, each of the lower layers adds a header (and sometimes a trailer) containing protocol information specific to that layer. These headers are called Protocol Data Units (PDUs), and the process of adding these headers is called encapsulation.

For example, the Transport layer adds a header containing flow control and sequencing information (when using TCP). The Network layer header adds logical addressing information, and the Data-Link header contains physical addressing and other hardware specific information.

The PDU of each layer is identified with a different term:

|

Layer

|

PDU Name

|

|

Application Layer

|

–

|

|

Presentation Layer

|

–

|

|

Session Layer

|

–

|

|

Transport Layer

|

Segments

|

|

Network Layer

|

Packets

|

|

Data-Link Layer

|

Frames

|

|

Physical Layer

|

Bits

|

Each layer communicates with the corresponding layer on the receiving device. For example, on the sending device, hardware addressing is placed in a Data-Link layer header. On the receiving device, that Data-Link layer header is processed and stripped away before it is sent up to the Network and other higher layers.

Specific devices are often identified by the OSI layer the device operates at; or, more specifically, what header or PDU the device processes.

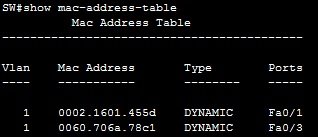

For example, switches are usually identified as Layer-2 devices, as switches process hardware (usually MAC) address information stored in the Data-Link header of a frame.

Similarly, routers are identified as Layer-3 devices, as routers look for logical (usually IP) addressing information in the Network header of a packet.

OSI Reference Model Example

The following illustrates the OSI model in more practical terms, using a web browser as an example:

• At the Application layer, a web browser serves as the user interface for

accessing websites. Specifically, HTTP interfaces between the web

browser and the web server.

• The format of the data being accessed is a Presentation layer function.

Common data formats on the Internet include HTML, XML, PHP, GIF,

JPG, etc. Additionally, any encryption or compression mechanisms used

on a webpage are a function of this layer.

• The Session layer establishes the connection between the requesting

computer and the web server. It determines whether the communication

is half-duplex or full-duplex.

• The TCP protocol ensures the reliable delivery of data from the web

server to the client. These are functions of the Transport layer.

• The logical (in this case, IP) addresses configured on the client and web

server are a Network Layer function. Additionally, the routers that

determine the best path from the client to the web server operate at this

layer.

• IP addresses are translated to hardware addresses at the Data-Link

layer.

• The actual cabling, network cards, hubs, and other devices that provide

the physical connection between the client and the web server operate at

the Physical layer.