Cognition

From Wikipedia

These processes are analyzed from different perspectives within different contexts, notably in the fields of

linguistics,

anesthesia,

neuroscience,

psychiatry,

psychology,

education,

philosophy,

anthropology,

biology,

systemics, and

computer science.

[1][page needed] These and other different approaches to the analysis of cognition are synthesised in the developing field of

cognitive science, a progressively autonomous

academic discipline. Within psychology and philosophy, the concept of cognition is closely related to abstract

concepts such as

mind and

intelligence. It encompasses the

mental functions,

mental processes (

thoughts), and states of

intelligent entities (

humans, collaborative groups, human organizations, highly autonomous machines, and

artificial intelligences).

[2]Cognition can in some specific and abstract sense also be

artificial.

[4]

Etymology[edit]

The word cognition comes from the

Latin verb

cognosco (

con ‘with’ and

gnōscō ‘know’) (itself a cognate of the

Greek verb γι(γ)νώσκω

gi(g)nόsko, meaning ‘I know, perceive’ (noun: γνώσις

gnόsis ‘knowledge’)) meaning ‘to conceptualize’ or ‘to recognize’.

[5]Origins[edit]

“Cognition” is a word that dates back to the 15th century when it meant “thinking and awareness.

[6] “Attention to the cognitive process came about more than twenty-three centuries ago, beginning with Aristotle and his interest in the inner workings of the mind and how they affect the human experience. Aristotle focused on cognitive areas pertaining to memory, perception, and mental imagery. The Greek philosopher found great importance in ensuring that his studies were based on empirical evidence; scientific information that is gathered through thorough observation and conscientious experimentation.

[7] Centuries later, as psychology became a burgeoning field of study in Europe and then gained a following in America, other scientists like Wilhelm Wundt, Herman Ebbinghaus, Mary Whiton Calkins, and William James, to name a few, would offer their contributions to the study of cognition.

Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) heavily emphasized the notion of what he called introspection: examining the inner feelings of an individual. With introspection, the subject had to be careful to describe his or her feelings in the most objective manner possible in order for Wundt to find the information scientific.

[8][9] Though Wundt’s contributions are by no means minimal, modern psychologists find his methods to be quite subjective and choose to rely on more objective procedures of experimentation to make conclusions about the human cognitive process.

Herman Ebbinghaus (1850–1909) conducted cognitive studies that mainly examined the function and capacity of human memory. Ebbinghaus developed his own experiment in which he constructed over 2,000 syllables made out of nonexistent words, for instance EAS. He then examined his own personal ability to learn these non-words. He purposely chose non-words as opposed to real words to control for the influence of pre-existing experience on what the words might symbolize, thus enabling easier recollection of them.

[8][10] Ebbinghaus observed and hypothesized a number of variables that may have affected his ability to learn and recall the non-words he created. One of the reasons, he concluded, was the amount of time between the presentation of the list of stimuli and the

[clarification needed]. His work heavily influenced the study of serial position and its affect on memory, discussed in subsequent sections.

Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was an influential American female pioneer in the realm of psychology. Her work also focused on the human memory capacity. A common theory, called the Recency effect, can be attributed to the studies that she conducted.

[11] The recency effect, also discussed in the subsequent experiment section, is the tendency for individuals to be able to accurately recollect the final items presented in a sequence of stimuli. Her theory is closely related to the aforementioned study and conclusion of the memory experiments conducted by Herman Ebbinghaus.

[12]

William James (1842–1910) is another pivotal figure in the history of cognitive science. James was quite discontent with Wundt’s emphasis on introspection and Ebbinghaus’ use of nonsense stimuli. He instead chose to focus on the human learning experience in everyday life and its importance to the study of cognition. James’ major contribution was his textbook

Principles of Psychology that preliminarily examines many aspects of cognition like perception, memory, reasoning, and attention to name a few.

[12]

Genetics[edit]

The

evolution of

human brain and cognitive function is driven by different networking or feedback processes underlying genetic and environmental system.

[13]Psychology[edit]

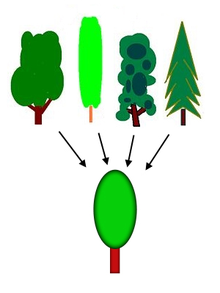

When the mind makes a generalization such as the concept oftree, it extracts similarities from numerous examples; the simplification enables higher-level thinking.

The sort of mental processes described as

cognitive are largely influenced by research which has successfully used this paradigm in the past, likely starting with

Thomas Aquinas, who divided the study of behavior into two broad categories: cognitive (how we know the world), and

affective (how we understand the world via feelings and emotions)

[disputed – discuss].

[citation needed] Consequently, this description tends to apply to processes such as

memory,

association,

concept formation,

pattern recognition,

language,

attention,

perception,

action,

problem solving and

mental imagery.

[14][15]Traditionally,

emotion was not thought of as a cognitive process. This division is now regarded as largely artificial, and much research is currently being undertaken to examine the

cognitive psychology of emotion; research also includes one’s awareness of one’s own strategies and methods of cognition called

metacognition and includes

metamemory.

Empirical research into cognition is usually scientific and quantitative, or involves creating models to describe or explain certain behaviors.

While few people would deny that cognitive processes are a function of the

brain, a cognitive theory will not necessarily make reference to the brain or other biological process (compare

neurocognitive). It may purely describe behavior in terms of information flow or function. Relatively recent fields of study such as

cognitive science and

neuropsychology aim to bridge this gap, using cognitive paradigms to understand how the brain implements these information-processing functions (see also

cognitive neuroscience), or how pure information-processing systems (e.g., computers) can simulate cognition (see also

artificial intelligence). The branch of psychology that studies brain injury to infer normal cognitive function is called

cognitive neuropsychology. The links of cognition to

evolutionary demands are studied through the investigation of

animal cognition. And conversely, evolutionary-based perspectives can inform hypotheses about cognitive functional systems’

evolutionary psychology.

The theoretical school of thought derived from the cognitive approach is often called

cognitivism.

The phenomenal success of the cognitive approach can be seen by its current dominance as the core model in contemporary psychology (usurping

behaviorism in the late 1950s). Cognition is severely damaged in dementia.

Social process[edit]

For every individual, the social context in which he or she is embedded provides the symbols of his or her representation and linguistic expression. The human society sets the environment where the newborn will be socialized and develop his or her cognition. For example,

face perception in human babies emerges by the age of two months: young children at a playground or swimming pool develop their social recognition by being exposed to multiple faces and associating the experiences to those faces.

Education has the explicit task in

society of developing cognition. Choices are made regarding the

environment and permitted

action that lead to a formed

experience.

Language acquisition is an example of an

emergent behavior. From a large systemic perspective, cognition is considered closely related to the social and human organization

functioningand constrains. For example, the macro-choices made by the teachers influence the micro-choices made by students..

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development[edit]

For years, sociologists and psychologists have conducted studies on

cognitive development or the construction of human thought or mental processes.

Jean Piaget was one of the most important and influential people in the field of Developmental Psychology. He believed that humans are unique in comparison to animals because we have the capacity to do “abstract symbolic reasoning.” His work can be compared to

Lev Vygotsky,

Sigmund Freud, and

Erik Erikson who were also great contributors in the field of Developmental Psychology. Today, Piaget is known for studying the cognitive development in children. He studied his own three children and their intellectual development and came up with a theory that describes the stages children pass through during development.

[16]

| Stage |

Age or Period |

Description |

| Sensorimotor stage |

Infancy (0–2 years) |

Intelligence is present; motor activity but no symbols; knowledge is developing yet limited; knowledge is based on experiences/ interactions; mobility allows child to learn new things; some language skills are developed at the end of this stage. The goal is to develop object permanence; achieves basic understanding of causality, time, and space. |

| Pre-operational stage |

Toddler and Early Childhood (2–7 years) |

Symbols or language skills are present; memory and imagination are developed; nonreversible and nonlogical thinking; shows intuitive problem solving; begins to see relationships; grasps concept of conservation of numbers; egocentric thinking predominates. |

| Concrete operational stage |

Elementary and Early Adolescence (7–12 years) |

Logical and systematic form of intelligence; manipulation of symbols related to concrete objects; thinking is now characterized by reversibility and the ability to take the role of another; grasps concepts of the conservation of mass, length, weight, and volume; operational thinking predominates nonreversible and egocentric thinking |

| Formal operational stage |

Adolescence and Adulthood (12 years and on) |

Logical use of symbols related to abstract concepts; Acquires flexibility in thinking as well as the capacities for abstract thinking and mental hypothesis testing; can consider possible alternatives in complex reasoning and problem solving.[17] |

Common experiments[edit]

Serial position

The serial position experiment is meant to test a theory of memory that states that when information is given in a serial manner, we tend to remember information in the beginning of the sequence, called the primacy effect, and information in the end of the sequence, called the recency effect. Consequently, information given in the middle of the sequence is typically forgotten, or not recalled as easily. This study predicts that the recency effect is stronger than the primacy effect because the information that is most recently learned is still in working memory when asked to be recalled. On the other hand, information that is learned first still has to go through a retrieval process. This experiment focuses on human memory processes.

[18]Word superiority

The word superiority experiment presents a subject with a word or a letter by itself for a brief period of time, i.e. 40ms, and they are then asked to recall the letter that was in a particular location in the word. By theory, the subject should be able to correctly recall the letter when it was presented in a word than when it was presented in isolation. This experiment focuses on human speech and language.

[19]Brown-Peterson

In the Brown-Peterson experiment, participants are briefly presented with a trigram and in one particular version of the experiment, they are then given a distractor task asking them to identify whether a sequence of words are in fact words, or non-words (due to being misspelled, etc.). After the distractor task, they are asked to recall the trigram which they were presented with before the distractor task. In theory, the longer the distractor task, the harder it will be for participants to correctly recall the trigram. This experiment focuses on human short-term memory.

[20]Memory span

During the memory span experiment, each subject is presented with a sequence of stimuli of the same kind; words depicting objects, numbers, letters that sound similar, and letters that sound dissimilar. After being presented with the stimuli, the subject is asked to recall the sequence of stimuli that they were given in the exact order in which they were given it. In one particular version of the experiment, if the subject recalled a list correctly, the list length increased by one for that type of material, and vice versa if it was recalled incorrectly. The theory is that people have a memory span of about seven items for numbers, the same for letters that sound dissimilar and short words. The memory span is projected to be shorter with letters that sound similar and longer words.

[21]Visual search

In one version of the visual search experiment, participants are presented with a window that displayed circles and squares scattered across it. The participant is to identify whether there is a green circle on the window. In the “featured” search, the subject is presented with several trial windows that have blue squares or circles and one green circle or no green circle in it at all. In the “conjunctive” search, the subject is presented with trial windows that have blue circles or green squares and a present or absent green circle whose presence the participant is asked to identify. What is expected is that in the feature searches, reaction time, that is the time it takes for a participant to identify whether a green circle is present or not, should not change as the number of distractors increases. Conjunctive searches where the target is absent should have a longer reaction time than the conjunctive searches where the target is present. The theory is that in feature searches, it is easy to spot the target or if it is absent because of the difference in color between the target and the distractors. In conjunctive searches where the target is absent, reaction time increases because the subject has to look at each shape to determine whether it is the target or not because some of the distractors if not all of them, are the same color as the target stimuli. Conjunctive searches where the target is present take less time because if the target is found, the search between each shape, stops.

[22]Knowledge representation

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Von Eckardt, Barbara (1996). What is cognitive science?. Massachusetts: MIT Press.ISBN 9780262720236.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Blomberg, O. (2011). “Concepts of cognition for cognitive engineering”. International Journal of Aviation Psychology 21 (1): 85–104. doi:10.1080/10508414.2011.537561.

- Jump up^ Sternberg, R. J., & Sternberg, K. (2009). Cognitive psychology (6th Ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

- Jump up^ Boundless. Anatomy and Physiology. Boundless, 2013. p. 975.

- Jump up^ Stefano Franchi, Francesco Bianchini. “On The Historical Dynamics Of Cognitive Science: A View From The Periphery”. The Search for a Theory of Cognition: Early Mechanisms and New Ideas. Rodopi, 2011. p. XIV.

- Jump up^ Cognition: Theory and Practice by Russell Revlin

- Jump up^ Matlin, Margaret (2009). Cognition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Fuchs, A. H.; Milar, K.J. (2003). “Psychology as a science”. Handbook of psychology 1 (The history of psychology): 1–26. doi:10.1002/0471264385.wei0101.

- Jump up^ Zangwill, O. L. (2004). The Oxford companion to the mind. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 951–952.

- Jump up^ Zangwill, O.L. (2004). The Oxford companion to the mind. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 276.

- Jump up^ Madigan, S.; O’Hara, R. (1992). “Short-term memory at the turn of the century: Mary Whiton Calkin’s memory research”. American Psychologist 47 (2): 170–174. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.2.170.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Matlin, Margaret (2009). Cognition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 5.

- Jump up^ Fareed M, Afzal M. (2014) Estimating the inbreeding depression on cognitive behavior: A population based study of child cohort. PLoS ONE 9(10):e109585.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109585 PMID 25313490

- Jump up^ Sensation & Perception, 5th ed. 1999, Coren, Ward & Enns, p. 9

- Jump up^ Cognitive Psychology, 5th ed. 1999, Best, John B., p. 15-17

- Jump up^ Cherry, Kendra. “Jean Piaget Biography”. The New York Times Company. Retrieved18 September 2012.

- Jump up^ Parke, R. D., & Gauvain, M. (2009). Child psychology: A contemporary viewpoint (7th Ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- Jump up^ Surprenant, A (2001). “Distinctiveness and serial position effects in total sequences”.Perception and Psychophysics 63 (4): 737–745. doi:10.3758/BF03194434. PMID 11436742.

- Jump up^ Krueger, L. (1992). “The word-superiority effect and phonological recoding”. Memory & Cognition 20 (6): 685–694. doi:10.3758/BF03202718.

- Jump up^ Nairne, J.; Whiteman, H.; Kelley, M. (1999). “Short-term forgetting of order under conditions of reduced interference”. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A: Human Experimental Psychology 52: 241–251. doi:10.1080/713755806.

- Jump up^ May, C.; Hasher, L.; Kane, M. (1999). “The role of interference in memory span”. Memory & Cognition 27 (5): 759–767. doi:10.3758/BF03198529.

- Jump up^ Wolfe, J.; Cave, K. & Franzel, S. (1989). “Guided search: An alternative to the feature integration model for visual search”. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 15 (3): 419–433. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.15.3.419.

Further reading[edit]

- Coren, Stanley; Lawrence M. Ward; James T. Enns (1999). Sensation and Perception. Harcourt Brace. p. 9. ISBN 0-470-00226-3.

- Lycan, W.G., (ed.). (1999). Mind and Cognition: An Anthology, 2nd Edition. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishers, Inc.

- Stanovich, Keith (2009). What Intelligence Tests Miss: The Psychology of Rational Thought. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12385-2. Lay summary (21 November 2010).

External links[edit]

|

Wikiversity has learning materials about Cognition |

|

Look up cognition in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Offline PDF Version

Offline PDF Version